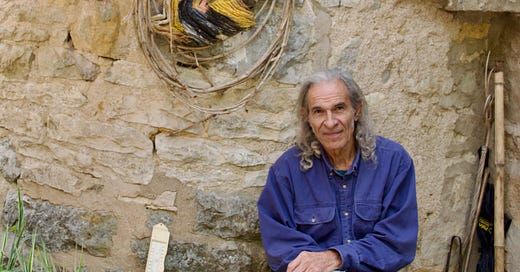

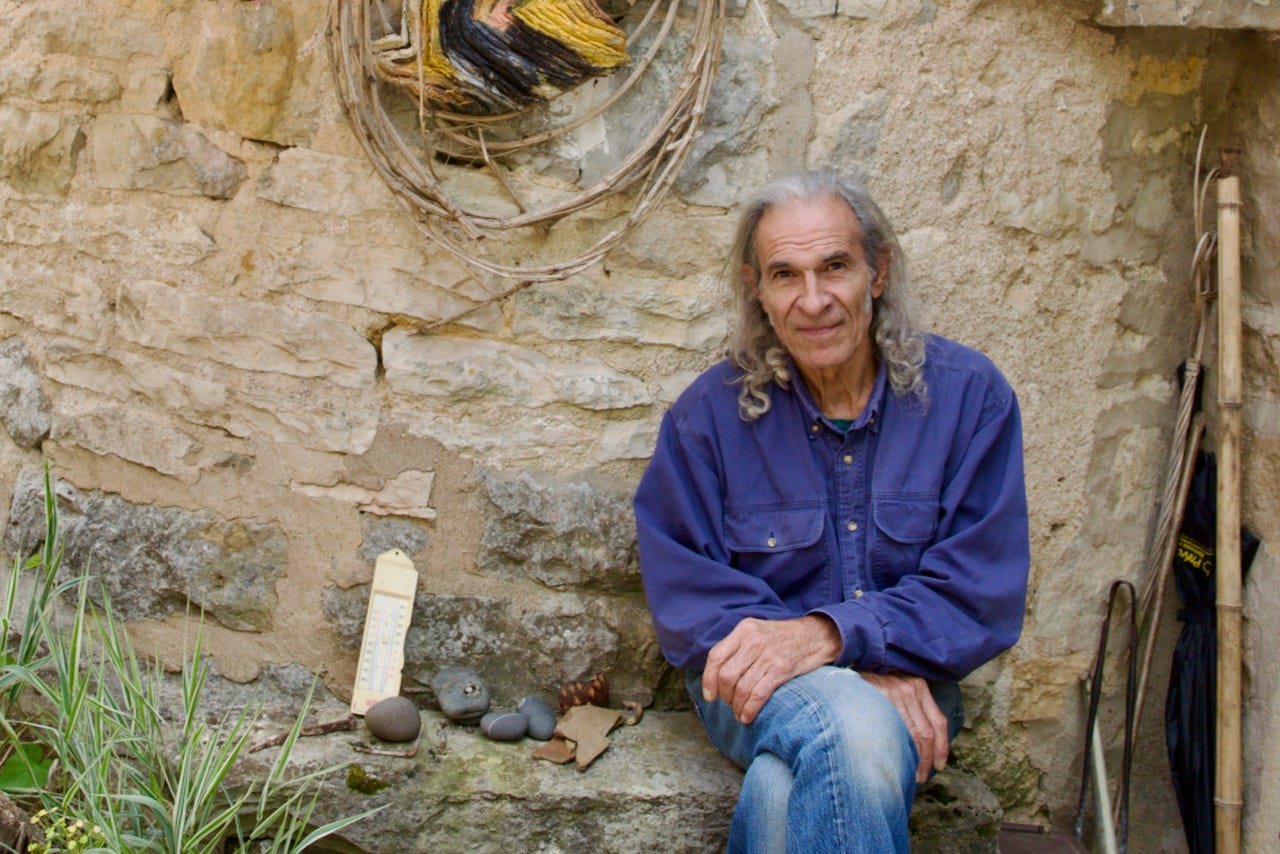

The Tao of Jean-Jacques Morel

Now retired, the Saint Aubin vigneron opens up about his unprecedented twenty-year experiment in no-till organic permaculture in the Côte d'Or.

Retired following the 2019 vintage, Saint Aubin vigneron Jean-Jacques Morel is what the French tend to call a UFO - by which they mean something unplaceable, unique, and inexplicable. Few in the French natural wine scene are aware of Morel’s work, because from his first bottled vintage in 2005, he sold about 80% of his production each year to export markets, mostly Australia and Japan.

Fewer still are aware of how radical Morel’s farming was. I learned only through Morel’s successor, Jon Purcell of Vin Noé, that Morel had been practicing Fukuoka-inspired, no-till organic permaculture, a form of farming with little precedent in modern Burgundy, even among organic and biodynamic peers. Morel doesn’t seem to have called much attention to his no-till farming during his active years - aware, presumably, of how ill-regarded it is in his community.

A former Parisian art dealer, Morel’s career as a vigneron spanned just twenty years. His wife Françoise works as a psychotherapist. He likes to travel, and made wine in Australia in the off-season for several years. These are lifestyle conditions that tend to incite neighboring Burgundian farmers to consider you a dilettante. The fact remains that Morel’s remaining wines represent a unique opportunity to taste great, naturally vinified Saint Aubin and Puligny cropped at yields that recall the mid-19th century.

Quick Facts

Born in Paris, Jean-Jacques Morel began working in viticulture in the 1990s, having decided, with his wife Françoise, to raise their family in the countryside. He worked for Pouilly-Fuissé estate Château des Rontets from 1995-1999, before moving to Saint Aubin when the opportunity arrived to plant a small surface of Saint Aubin “Les Combes au Sud” owned by his father-in-law.

In 2004, with a tip from his neighbor Dominique Derain, he obtained a lease for another 1.6ha. From then until 2015, he farmed a total 2.7ha, in Saint Aubin and Puligny-Montrachet.

From 2015 until 2019, Morel’s last vintage, he farmed just 2ha.

Morel’s first bottled vintage was 2005. He sold almost all of it to one Japanese importer. Throughout his career, his wines would remain little-known within France, finding greater renown in Japan and Australia.

Morel practiced organic farming from the start. Notably, he read Masanobu Fukuoka as far back as 2003, and drew inspiration from the Japanese farmer’s “do nothing” philosophy. Morel never owned a tractor, and never plowed his soils, instead working with a combination of mowing (six or seven times per season) and hoeing.

Yields were very low throughout his career, between 9HL-28HL/ha. (For comparison, the maximum yield, which is effectively the yield which all conventional farmers aim to slightly exceed, for Puligny-Montrachet in 2021 was 57HL/ha.) Morel notes that he never fully lost a harvest due to fungal attack, an achievement he credits to his maintenance of grass cover.

Morel never practiced filtration, or employed winemaking additives, other than a sulfite addition of 15-20mg/l before bottling on his white wines. He never sulfited red wines, which saw whole-cluster maceration with pigéage, before aging in used barrel. His whites saw long fermentations and elevage, usually around two years.

Morel’s hands-off, empirical, quasi-mystical approach to wine production extended into the cellar, where he professes not even to have measured must densities. His wines are Burgundian outsider art, offering glimpses of a bygone, less professionalized, yields-obsessed era. The highlights - like the 2019 Saint Aubin rouge - are very high indeed.

From 2015-2020, Morel produced négoçiant wine in Australia, aided by friends like Anton Van Klopper and Jasper Button.

Retired following the 2019 vintage, Morel transferred several of his vineyard rentals, and his cellar, to Jon Purcell of Vin Noé.

JEAN-JACQUES MOREL: AN INTERVIEW

The following interview was conducted in August 2021 and May 2022. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.

How did you come to be a vigneron in Burgundy?

JEAN-JACQUES MOREL: I was working for estates in Burgundy at the time. And my father in law lived here. He had parcels of vines, but he was not a vigneron. He was just an owner. He had renters. And he indicated that there were parcels that were freeing up. The rentals were stopping. So he suggested I come recover the parcels.

I didn’t hesitate too much. I arrived here in 1999. At the time there were two parcels. I started by planting a parcel that had been uprooted, it’s called “Les Combes au Sud.” Jon [Purcell] farms it now. It had been planted to red before it was uprooted. I planted it to chardonnay when I arrived.

The other parcel is above the house. It’s Saint Aubin 1er cru “La Chatenière.” It had been left as a prairie in the 1930s, so it spent sixty years as a prairie. There were horses and sheep. The story is that in the 1930s, there were enormous floods. Lots of water came down. And since there were vines all along the hill above the houses, with the floods, all the earth came down, and people had mud in the houses. So they decided, at that time, to uproot the vines and let nature take over. To let grass come in, to avoid that.

In 2001, I planted it. Then other estates started to plant it too. I put in protection when I planted, I put in a gutter. But for me the idea was to work with nature, with natural grass cover. So I’ve never had erosion at all.

Where did you learn to make wine?

Learned is a big word. I’d say I had observed a lot. I’d harvested with friends in the Beaujolais, I’d assisted Dominique Derain, and I’d harvested with a Quebecois called Pascal Marchand, who has an estate now. At the time, in 1995, he was the manager of Clos des Epeneaux in Pommard. I harvested and vinified with him twice. It was rather like that that I learned.

I also took a course to learn the work of the vine and the cellar. But that was just notes in a notebook, lists of products to apply in the vines, lists of products to apply in the cellar.

When you began, did you already seek to make wine without additives?

Oh yes. From the start. For me, wine is grapes. That’s all.

I was determined to add no product, chemical or otherwise, in my wines. No sugar, no yeast. Nothing that was not from nature. And no sulfur, for red wines. But I retained one little fear, and until the end, I sulfited the whites at the bottling, from 1.5g-2g/HL. In fact, it’s just a fear. Because it helps nothing.

And no filtration?

Filtration, I can’t even imagine it. A wine is flayed, it has no character after filtration.

Filtration arrived in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and from then on, people started to filter very tightly, and the wines became very fragile. So you had to put it more sulfites. If you don’t filter, there’s no need to add sulfites. It’s totally simple.

Most are too afraid of taking risks like that in Burgundy.

Risks, anyway, risks exist. Even if we don’t seek them, they exist. Look at 2021, with the mildew. No one sought it out. But there was a risk. You have to try to contain it. I had accidents on certain wines. I threw away wines. That happened.

Your approach to viticulture was also very fearless, in terms of risk.

I tried to observe. According to the weather, and what was happening to the earth. And I worked with the grass. I’m persuaded that leaving the grass diminishes the risk of mildew. Because mildew is not in the air. It’s in the earth, beneath a fine skin of earth. When spring arrives, rain falls, and the drops makes a crown of projection when they hit the bare earth, and it projects the mildew spores. But when there’s grass, there isn’t this phenomenon.

This is just observation. It’s empirical, there’s nothing scientific about it.

You found that when vineyards were grassed over, you had less mildew?

Completely. I never was infested. I never lost a harvest from mildew. I had a little bit on the upper leaves at the end of the season. But I didn’t care about that.

Did you truly never plow your soils?

No, no. The fact of not plowing, for me, corresponds to a respect for life. I had a crawler track vehicle, with turbine for copper and sulfur treatments. And when there were plants that seemed invasive or bothersome, I used a hoe.

Maybe you have heard of Fukuoka? He was an inspiration.

When did you read Masanobu Fukuoka?

I read him back in 2003-2004. Right when I was starting. I read many things. And I was already into many ideas that were considered “alternative.”

Reading about Fukuoka’s experiments was impressive. Because effectively, they ran counter to the approach of the totality of the farming profession, with certain rare exceptions like Dominique Derain, who was already interested in biodynamics.

Did you take an interest in biodynamics?

My position on biodynamics is particular. I had also read Steiner’s Agriculture Course. Or I tried to. There were a lot of things I didn’t understand well. But what I felt, reading Steiner, is he was telling farmers to stop going into routinized schema. To open your eyes, look at your environment, and try to adapt yourself to it. From what I understand of biodynamics nowadays, people who become disciples of Steiner tend to announce recipes. They changed the recipe. But they continued with recipes. For me, Steiner is not that.

I went to hear Pierre Masson speak, and discuss with him. And I bought things for tisanes, etc. But otherwise I tried to make my own tisanes, not necessarily the ones prescribed by biodynamics.

How did neighbors respond to your approach to farming?

There were many stories. Several times, the neighbors complained to the syndicat of the Puligny-Montrachet appellation. I think it was due to neighbors who were afraid of being invaded by grass. I received letters from the verification companies, who threatened to remove the appellation from my wines if I didn’t do anything about the too-big quantity of grass that was in my vines.

My only response was to tell them that I was going to mow the grass soon. And I waited for the good moment, and I mowed. I still had a mower.

You’ve also made wine in Australia. What were your impressions of viticulture there, compared to Burgundy?

It’s very, very interesting. To go observe and see how they work and how they envisage things. I bought grapes regularly from a biodynamic estate called Smallfry. Wayne Ahrens, who runs it, he’s lucky. He’s just at the frontier between Victoria and South

Australia. He has vines that are mostly on sands, so there’s no risk of phylloxera.

So he has vines that are 130 or 140-years-old. I saw that for the first time in my life. Here in Burgundy, people say vieilles vignes at forty-five years. Because after that it doesn’t yield enough for them and they uproot. Out there they have 140-year-old vines with grapes! I said, “Wow, I want that.”

It’s a shame I’m not younger and I can’t go install myself definitively out there. But voilà, that’s life.

FIN

Jean-Jacques Morel

8, rue de la Chatenière

21190 SAINT AUBIN

FURTHER READING

James Scarcebook did a nice English-language podcast with Jean-Jacques Morel in 2018 at Intrepid Wino. Take note of Morel’s tone of voice when he admits he owns no tractor.

A profile of Jean-Jacques Morel at the site of his Australian importer, Vinous.

My interview with Jon Purcell of Vin Noé, Morel’s successsor.

A photo-essay of a biodynamic spray treatment with Morel’s Saint Aubin neighbors Julien Altaber and Dominique Derain.