From San Diego to Saint Aubin: Vin Noé

After years working as a négoçiant, Californian expat Jon Purcell came into his own in 2020-21, taking on vineyards and a cellar from no-till organics legend Jean-Jacques Morel.

Emerging at the forefront of a new generation of talented expat natural vignerons in Burgundy is Vin Noé’s Jon Purcell, a kindhearted, full-bearded southern Californian with a flair for patient natural vinification. He began making wine in 2016, initially in collaboration with our friend Chris Santini, who lent him cellar space in Auxey. Purcell earned applause for his non-carbonic, whole-cluster “Burgundian” touch with gamay, and soon saw similar success with pinot noir and aligoté.

Purcell’s wine production took a quantum leap forward in 2020, when he recovered 0.80ha of vines from Saint Aubin no-till organics legend Jean-Jacques Morel. Last August, he moved into Morel’s former cellar in the village of Gamay, even as he began releasing his first wines from Morel’s low-yield, longtime-organic parcels of Saint Aubin and Puligny-Montrachet.

Although he’s in fact a few years younger than me, I tend to consider Purcell kind of a big brother figure. Preternaturally calm, competent, and modest, he’s spent the last decade doing what I’d quite like to do this decade, namely move to rural France, start a family, and begin making wine on a boutique scale. I count myself blessed that he’s always been ready to share his friendship, his Burgundy savoir-faire, and, lately, his winemaking supplies. I am, in short, not an impartial judge of his gorgeous wines.

Quick Facts

Originally from Oceanside, near San Diego, Jon Purcell moved to Burgundy in 2012, after work experience in Napa at White Rock Vineyards.

He enrolled in the BPREA program at Beaune Viti, but didn’t finish it, instead doing work experience with David Croix and Philippe Pacalet. Later he worked for years as a tractoriste for Domaine de Montille and Domaine Matrot.

With the help of his friend, the Kermit Lynch export manager and négoçiant winemaker Chris Santini, Purcell began making négoçiant wine in 2016, a collaborative cuvée of Beaujolais-Villages from Lantignié, produced in Santini’s cellar in Auxey. In 2017, Purcell produced two wines as Vin Noé: a macerated viognier from southern Beaujolais, and a Juliénas. In 2018, Purcell began producing a ripe aligoté from Bouzeron, and another Beaujolais, from Bully in the Pierres Dorées. In 2019, he debuted a Bourgogne rouge from grapes in the Côte Chalonnaise, and a Pommard.

In 2020, he began farming vines recovered from retiring Saint Aubin vigneron Jean-Jacques Morel, including Saint Aubin 1er cru “La Chatenière,” Saint Aubin 1er cru “Les Combes,” and a high-sited parcel of Puligny-Montrachet, “Le Trèzin,” in Blagny.

Today, Purcell’s total vineyard surface is 0.80ha. He hopes to plant another 20 ares early next year. Farming remains organic, although Purcell has begun working the soil about four times per year in efforts to restore vigor.

In 2021, just in time for harvest, Purcell moved into Jean-Jacques Morel’s former cellar in the village of Gamay, beside Saint Aubin.

For white vinification, Purcell favors minimal débourbage, if any, preferring to ferment wines in barrel on gross lees. For reds, he vinifies whole-cluster, with pigéage, in small foudre, steel, or fiberglass tank, before aging in used barrel. He hasn’t employed sulfites in vinification or at bottling since, once, adding 30mg/L to his first Juliénas; nothing is ever filtered.

Total production in 2021 was 90HL.

FROM SAN DIEGO TO SAINT AUBIN

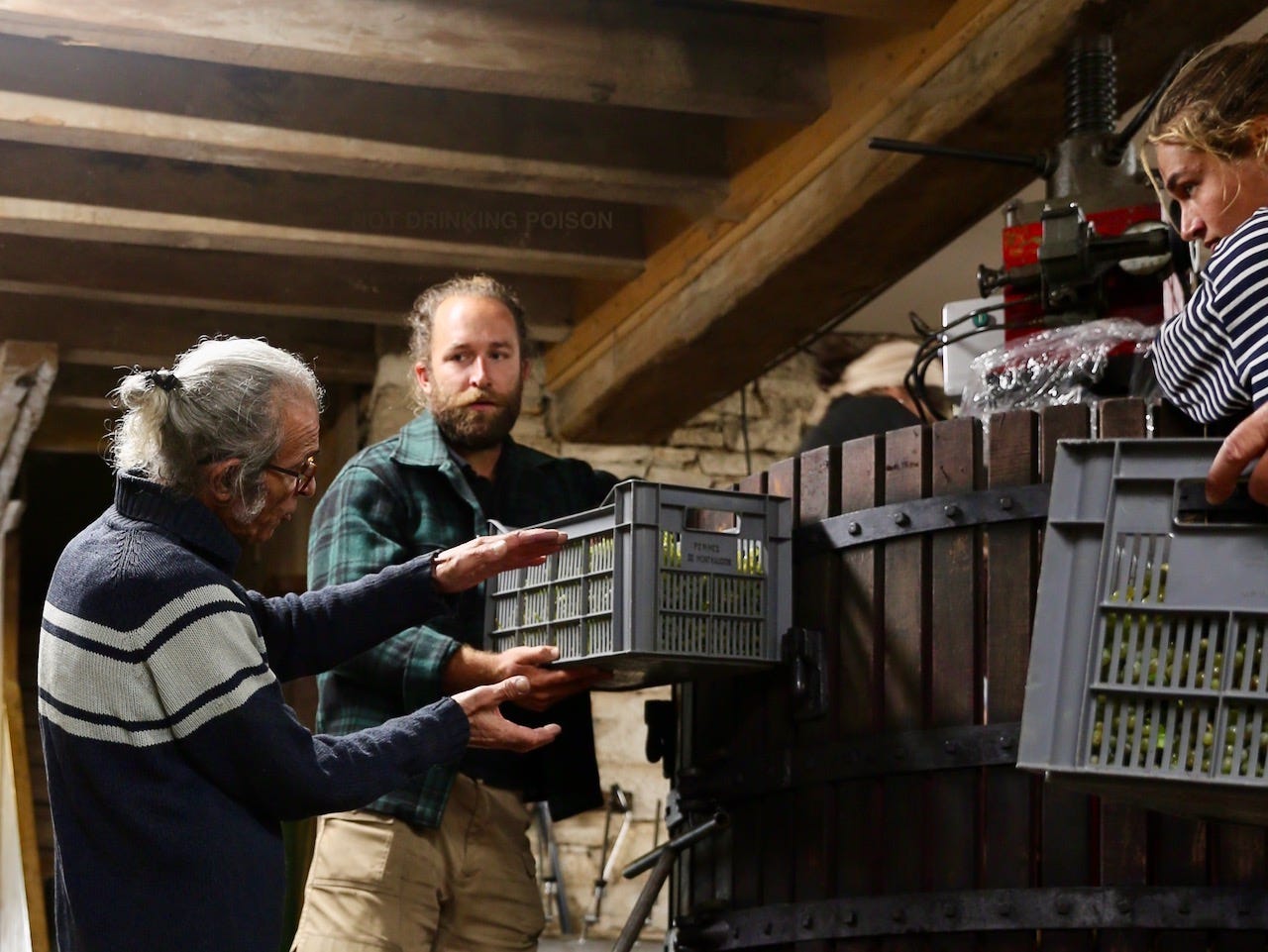

When I arrive to his new cellar in the village of Gamay, Jon Purcell and his Burgundian father-in-law are already at work, cleaning Purcell’s spanking-new, motorized vertical press. Purcell assures me there will be more work to do, but I suspect my presence is, as usual, totally superfluous to the tasks at hand. I initially meant to join Purcell for the entire harvest period. But I’d gotten bogged down in Faugères with the opportunity to make a tiny quantity of my own wine, with the result that by the time I make it to Burgundy, all that’s left to do is de-vat and press.

2021 has been a big year for Purcell: he became a father, quit his day job as a tractoriste for Domaine Matrot, and moved into the former cellar of his vineyard predecessor, Saint Aubin vigneron Jean-Jacques Morel. I feel remorseful for not being around more, even as I know Purcell is surrounded by friends and supporters in the area. Today in the cellar he and his father-in-law work with a sort of terse, sublingual efficiency, testifying to how often the latter has been volunteering this season.

When the press is clean, Purcell’s father-in-law departs on an errand, and Purcell hops into a small steel vat of a new purchase of Côtes de Nuits Villages, devatting with a bucket into the press. The wine is darker than most, this cool vintage. Mildew issues caused Purcell to press his Bourgogne rouge after a very short maceration, yielding a wine so pale he debated whether to call it a rosé.

Months later, Purcell would remark that he actually prefers this new style of light red vinification he stumbled upon - for the Bourgogne rouge, at least. Until now, Purcell’s red vinification has been distinguished, among his zero-zero peers, for a slightly greater extraction than is fashionable with whole-cluster vinification. (It’s tempting to suggest this faith in traditional pigéage is a legacy of Purcell’s time working for Philippe Pacalet, although Purcell makes very little of the connection and tends to downplay it in conversation.)

Purcell’s approach to white vinification is more experimental. In 2017 he debuted with an intense, cognac-toned macerated viognier called “Face to Face,” an orange wine that owed more stylistic debt to the Friulian school than to the lighter, brisker styles that dominate in Alsace and Central Europe these days. More recently, in 2020, he produced a macerated chenin from vines situated in Meursault (apparently a micro-parcel belonging to a great fan of chenin liquoreux.) Purcell even went so far as to macerate the 2020 chardonnay from the Saint Aubin 1er cru “La Chatenière.”

I find Purcell’s direct-press white work to be his most distinguished and his most radical, simply for its combination of patience in élevage and refusal of sulfite addition. He tends to practice little, if any débourbage, preferring the inclusion of lees to help carry his whites through their long evolution in barrel. His Puligny-Montrachet in particular is a piercing, stony, anise-toned triumph, a true peer to the work of Renaud Boyer.

Purcell’s Puligny parcel itself is something to behold, high on the hill in Blagny. Jean-Jacques Morel recounted, when I spoke to him in late summer, that back in 1999, when he took over the parcel, the old folks in the village recalled its wines being more sought-after than the 1er crus down below. (To be fair, most old villagers, in any village, say this about any vineyard in said village.)

Back in Gamay, my role is limited to handing things to Purcell as he de-vats the Côtes de Nuits Villages. I’ve missed the season here, so I plan to leave in the following days to join the Maule family in the Veneto for their final week of harvest.

I’ve known Purcell since 2016 or so. If I haven’t written anything about him before, it’s because it’s hard to write about the work of friends. I also have a certain anxiety about appearing overly boosterish about expat winemakers, who tend to make for facile copy simply by dint of being expats. But the fact is today Purcell is part of an extremely talented, cosmopolitan, and photogenic circle of expat winemakers in Burgundy, including Christian Knott, Bastien Wolber, Chris Santini, Andrew and Emma Nielsen, Tomoko Kuriyama, Joachim Skyaasen, and more. (Not to mention Katie Worobeck in the Jura.)

Together, these winemakers comprise a scene that is newsworthy in itself. But in taking on Jean-Jacques Morel’s vineyards in 2020, Purcell became heir to a different story. His magnificent estate whites - two Saint Aubins and a Puligny-Montrachet - today comprise the coda to Morel’s two-decade experiment with no-till organics in Burgundy. It’s something the wine world should be watching.

JON PURCELL: AN INTERVIEW

This interview was conducted on May 3rd. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What’s the origin of the name Vin Noé?

It’s sort of a tribute to my grandparents. Noé was the last name of my great-grandmother on mother’s side. My family are all in the south and are a total hodgepodge of ethnicities and origins. But Noé is the French side of the family.

What did you do before moving to Beaune in 2012?

I studied political science. But I was interested in winemaking before that. I went to Northwestern to play baseball, otherwise I would have gone to Cal Poly or UC Davis. But it was hard to turn down the baseball scholarship.

I made the best of it. But as soon as I could leave, I went to back to California and went into wine. When I left school, I had the choice between working for a courthouse, and working for a wine importer. So I blew off my thesis and went to Napa. I worked for Beaulieu Vineyards. But my first real winemaking experience was with White Rock Vineyards.

What impelled you to move to Burgundy?

It’s kind of multi-faceted. I really liked Burgundy wine, even though I was living in CA. My dad had a lot of Burgundy, so my first references for really good wine was Burgundy. I think I first went to Burgundy on my own when I was twenty. And I was really welcomed into the whole foreigner circle, and it was really fun. So it was an easy choice.

Were there things about Burgundian wine culture that shocked you, having moved from Napa?

Even while some Burgundian estates are quite modern, they’re still less interventionist than in America. I Burgundy they would never do the things I saw when I worked in Napa.

And the wine culture, as you know, in America it has less of it’s own ingrained ideas and inertia and all that stuff. When you work harvest in burgundy, it’s a little more all-consuming. You can feel the whole tradition, the amount of time they’ve been making wine, compared to harvest in a new world setting.

Were you already aware of the notion of natural wine when you moved to Burgundy?

I’d had natural wines before, and I knew that I liked them, but I didn’t have a super strong idea about it. It was more in Beaune that I discovered it. Among my classmate at the Lycée in Beaune that year there were quite a few sons and daughters from big natural wine estates in the Beaujolais. The other person who really showed me a lot of natural wine was Christian [Knott, of Domaine Chandon de Briaille]. Just hanging out with Christian, and Andew Nielsen [of Le Grappin]. I did a trip to Ardeche my first year here, and visited Gilles Azzoni, and Jerôme Jouret, and went to some bars, and went rock climbing. That kind of made up my mind.

What’s your own approach to sulfitage in winemaking?

The 2017 Juliénas was the only wine ever I sulfited. I added a total of 3g/HL. And since then, never. I just never appreciated anything sulfites did to a wine. It was just that in all of my previous experiences, everybody would dabble with sulfites. So the first year, I did what I knew how to do. Then I abandoned that.

How did you meet Jean-Jacques Morel?

My last year at Domaine de Montille, we had an intern from New Zealand called Casey, and we got along pretty well, and she had a friend called Ashley who worked for Jean-Jacques. So at the end of Casey’s internship, we had going-away drinks, and Jean-Jacques came. We got along pretty well, and we exchanged tastings, and had dinner together. When I had dinner at the Morels’ place, sometime after midnight, they were like, “What do you think about taking over the vines and cellar?”

What were your impressions when you first saw his vines?

I thought they were really beautiful. Because they were the opposite of everything anybody does here. They were relatively low in vigor. You could tell there weren’t that many grapes. But what stood out was the health of the soil and the diversity of the plant life in the soil. It’s still there, even with the return to plowing. You’d have to ask him the last time he plowed, but I think it was at least ten years ago, and I think that’s to the benefit of what I’m doing now. What he was doing was really unique.

I don’t do the same, but I’m trying to adapt it, to make it financially viable, without turning it into the industrial-organic you see all the time.

How have you adapted the viticulture?

The first year I took over, I plowed it all by horse. Now after a couple years of finding better solutions, the Puligny and “Combe” are horse-plowed, and I work “La Chatenière'“ with hoe and cable plow. But it’s pretty minimal, just four times per year. It’s the least you can do in Burgundy. Unless you do nothing.

0.80ha is a very small vineyard surface. Do you have plans to acquire new parcels?

I haven’t signed for it yet, but I’ll start leasing another unplanted parcel from Jean-Jacques. It’s 20 ares of Bourgogne, which would make exactly 1ha, which is nice on paper. We’ll plant that early next year. I’m planning to plant it field-blend style: about half pinot noir, a third trousseau, and the rest aligoté, chardonnay, and gamay.

FIN

Vin Noé - Jon Purcell

8, rue de la Chatenière

21190 SAINT AUBIN

FURTHER READING

Some excellent photographs of Vin Noé on the site of his UK importer, Sager and Wine.

An interview with Purcell’s predecessor Jean-Jacques Morel.