The Abandoned Orchards of UTOPIA

Ten questions for Ivo Laurin, who with his wife Eva produces unsulfited, unfiltered, un-enzymed Czech Republic ciders from untreated and abandoned orchards where south Bohemia meets Moravia.

Eva and Ivo Laurin produce natural cider and cider vinegar as UTOPIA on a majestic farm dating to the 15th century outside the village of Obrataň - a short walk through the woods from where my friends Jan and Nada Klimes produce EUFORIA birch saps. Apparently both couples fled the city life in Prague at around the same time; upon meeting in their new surroundings, they quickly became friends and colleagues on the frontier of Czech Republic neo-paysan artisan beverage production.

The UTOPIA cider production is notable for the Laurins’ deft exploitation of the regional particularities of their situation, notably the late ripening period, the reliably intense winter chill, and the proximity of numerous and diverse old orchards, unfarmed or abandoned outright.

Back in mid-January the Laurins kindly hosted us around their cosy kitchen table for a splendid tasting of ciders, infused cider vinegars, and Eva’s delectable meringue cake.

Quick Facts

Ivo and Eva Laurin moved to their farm from Prague in 2013. After forays into many mixed-agriculture endeavors, including bee-keeping and raising carp, they alighted on cider production (and later that of artisanal cider vinegar). Their first vintage (uncommercialized) was 2015; they began selling their ciders in 2016, their first vintage produced with zero additives.

Ivo maintains a role running a Prague-based ad agency he co-founded called Outbreak, a business name he presumably regretted in 2020-2021. Eva, for her part, formerly worked in the automotive industry as a quality manager.

In 2016, Ivo completed a training course in at cider authority Peter Mitchell’s UK-based Cider Academy. There he learned the fundamentals of conventional cider production, much of which he would reject in his work as UTOPIA.

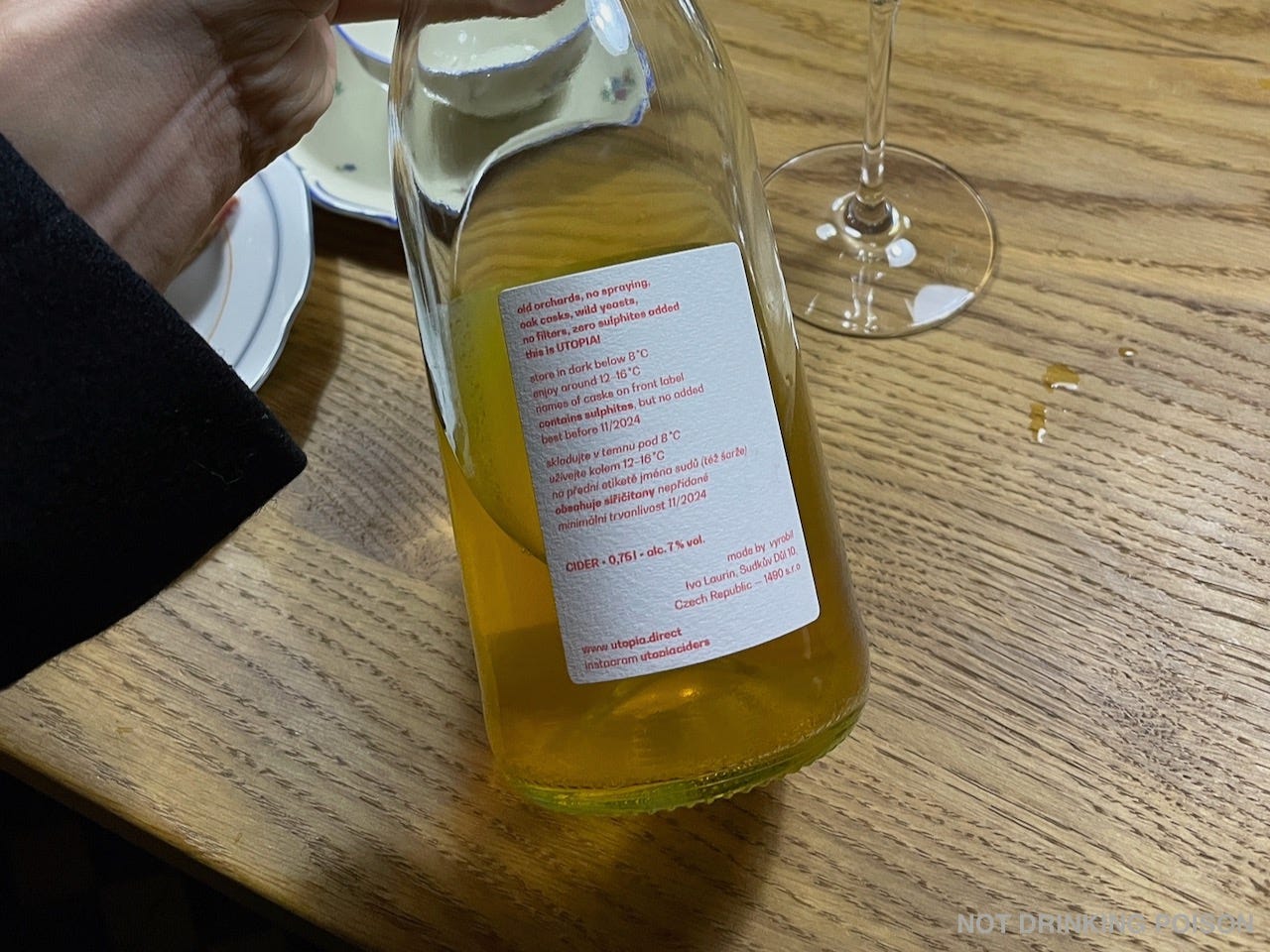

UTOPIA cider production is divided into four categories: still dry ciders, sparkling dry ciders, cider and grape marc co-ferments and infusions, and ice cider. Nothing is filtered, nothing is fined, nothing is sulfited; the Laurins also do not employ pectic enzymes for clarification. Some cider cuvées are produced using a layer of straw from a nearby hill in the press to filter and further inoculate the cider must with wild yeasts.

Eva takes the lead producing the couple’s vinegars, which are produced to a similarly exacting standard, and which she infuses with a variety of foraged ingredients.

Total production in 2022 was 10,000 bottles.

The great question in front of any natural cider producer is: why purchase cider from where you are, rather than the from many other places throughout Europe that make reasonably distinctive cider? The Laurins do a good job answering this question.

IVO LAURIN of UTOPIA: AN INTERVIEW

When did you move to Obrataň?

We came here almost eleven years ago. We started with all sorts of animals and plants. We had geese and ducks and sheep and bees and fish. Then we started making cider, and we had to pretty much pause all the other activities, because it was too much.

From the start, the idea was to produce something that was okay to eat: no chemicals, no bullshit.

When did you begin producing cider?

The first vintage was 2015, it was 500L, only for friends and family. I bought everything: the sulfur sticks, and selected yeasts, everything. I didn’t know. I had these 50L demijohns, and when I lit the first sulfur stick, I was like, “I’m not putting that in there.” So I skipped that. We inoculated half the production with select yeasts, and the other half we let ferment spontaneously. We felt the yeasted stuff was like ciders we’ve already known, to some extent, whereas the spontaneous stuff felt more interesting and unknown. So we decided to go that way after a couple of months.

For now you’re purchasing apples?

Yes. Our only orchard is the one we planted five years ago with Nada and Jan [Klimes, of EUFORIA]. It’s 2.5ha.

All the other places we source apples are either orchards or gardens. We had a company make us a cadastral map, so we could start exploring which orchards cited in the cadastre were still orchards. And we start going around and getting in touch with all these owners. The first orchard we started to work with about four kilometers away, in the valley.

You’re just going door to door?

Yes, we do that too. But there’s tons of apples. There’s forty years of communism behind us. No one knew what to do with the land. They would grow varieties that are not really nice for eating. A lot of it was used to feed cattle. So there’s all sorts of strange old varieties. Each vintage now has about fifty different varieties, on average.

When is normal harvest time around here?

It depends on the variety of apple, of course. But we start in October, because we tend to like the later varieties more, they’re the best for us.

Do you age the apples before crushing and pressing?

With some varieties we do that. But most of the varieties that we work with, since they come in from mid-October until the third week of November, they’re sitting here for one weeks, two weeks, or at most three. One reason is we we work with tall old apple trees. Some of them are eighty-five years old, and they’re quite high. So when the apples fall, they bruise [making them unsuitable for aging].

Here you don’t have the same varieties that were selected for cider making, like they have in England, where you can see many of the varieties lying in huge volumes on concrete floors outside, and they take them in using machines, almost like potatoes. That’s not the case here. The apples are more delicate.

Are you self-taught, as a cider maker?

I’m primarily self-taught. I also learn from discussions with Milan [Nestarec] and other winemakers. But I did go to England to this Cider Academy. I have a diploma over there to show the health authorities. Because they don’t know shit about winemaking or cider-making. They take care of restaurants or industrial producers. So when they come here it’s good to show them this.

I was pretty scared when I went [to the Cider Academy], because it was the winter after the first vintage. I kept asking, “What if I didn’t do this, or what if I didn’t add this?” and he always replied, “Don’t do that.” He didn’t even want to talk about it. But there’s a place in the world for his teaching.

The names on your labels are not the apple variety names, as I understand.

No. It’s a fifty variety situation. In the beginning we were bottling every single cask into a small batch of three-hundred bottles, and there were forty casks. We decided to give the casks the names of women who lived on this farm over the past four-hundred years. We were able to identify their first names, so we put them on the casks.

So the name of the bottling is the name of the cask - or two cask names, because since two years ago we started blending the casks. We start to feel like we know what the various varieties are like, so now we are blending.

So you formerly made more single-variety ciders, when you were beginning?

In the beginning, we needed to figure out which varieties or orchards were good, so we did everything as single cask bottling, and just still cider, not covered by layers of the bubbles. To be able to say what works and what doesn’t.

That was the first style. We do less and less still cider, because it’s not that popular. But we drink it at home, we like the nuances.

It’s not usual to make single-variety ciders. We make one from a very old variety called panenské české, or “Czech virgin.”1 It’s a small red apple. So the amount of flesh is smaller, relative to skin. It's a really old variety, no one knows here it came from. It’s one orchard, five kilometers towards Tábor. They have three trees. All the Czech virgin apples that we get are from those three trees. This past autumn we were able to get six casks, the most we have ever had.

It’s a really fragrant variety, I can tell when I have it in the press. It has a distinct aromas in the glass as well. Then we also make single varietal ciders with two other varieties.

Your sweet ice cider is very unusual, for being neither filtered nor sulfited to prevent fermentation. How do you make it?

We freeze the juice before it starts fermenting, and then we let it thaw outside, and we draw off the juice. The water stays there. [Ed.: The part with the highest concentration of sugar, and thus the lowest freezing point, thaws first.]

We take the first 200L fraction for the ice cider and put it in cask. It doesn’t ferment, because it was frozen to minus 20°C, so we take 1L of fermenting cider from the same vintage from a nearby cask to inoculate it. It’s a dessert cider, 10% alcohol, with huge acidity, because it doesn’t do malolactic.

It takes two years to produce. Every winter, we pump all the casks outside, and let them sit there two weeks, then we pump it back in, and it ferments for another year, and when we do it a second time, it doesn’t referment in the bottle. So no filtration, no sulfites. I think it’s one of the only commercially-produced ice ciders made this way. Usually they filter, they add all sorts of stuff.

FIN

UTOPIA - Eva & Ivo Laurin

Sudkův Důl 10

39501 OBRATAN

Czech Republic

FURTHER READING

A Taste of EUFORIA: An interview with Jan Klimeš

Lots of good information on specific UTOPIA cuvées at the site of their US importer, Jenny & François Selections.

Best to use the original Czech phrase when googling this.