Remembering Alain Castex

An archive interview with the pioneering natural vigneron of Banyuls and the Roussillon, who passed away this morning.

Legendary Roussillon vigneron Alain Castex passed away in his vines this morning at the age of 73. The cause was a heart attack. With him goes a half-century of experience in organic viticulture and natural winemaking, spanning the culture’s adolescence in the Beaujolais and the Loire in the 1990s to its present kaleidoscopic global diversity. In particular, his trailblazing work from 1995-2015 as Casot de Mailloles with then-companion Ghislaine Magnier in Banyuls-sur-Mer would inspire successive generations of natural winemakers in the Pyrénées-Orientales.

Alongside his peer Bernard Bellahsen, Castex is today recognized as a key forerunner of natural winemaking in the south of France. Yet his winemaking is unique, among his generation, for having become more prescient and stylistically relevant with the passing years. His delicate, low-alcohol, radically pure, white-kissed reds have become touchstones for younger natural winemakers in the Roussillon and beyond.

I interviewed Castex in October 2019 as part of research for the The World of Natural Wine. In the spirit of remembrance for Castex’s inspiring work, I thought I’d share the full interview for subscribers below.

While I was not personally close with Castex, I find myself citing his example often, particularly when people ask me to define “natural wine.” The best definition I can think of is an episode that occurred in 2010 at the wake of Marcel Lapierre, when Loir-et-Cher vigneron Thierry Puzelat and Alain Castex reportedly got into a violent dispute about volatile acidity.

What is natural wine? It is Thierry Puzelat getting into a fistfight with Alain Castex at the wake of Marcel Lapierre.1

Godspeed, Alain! I think you won.

Quick Facts

Alain Castex began his career as a vigneron in 1981 in Corbières at the age of thirty-two. Previously he’d worked as a mechanic and a truck driver and, briefly, for the SNCF.

He converted his Corbières estate to organic agriculture in 1989.

Castex began conducting tests of vinifications without added yeast or sulfites in the early 1990s, following an inspirational meeting with famed Burgundy enologist Max Leglise.

Castex’s final vintage in Corbières was 1994. He sold his estate, which had grown to 13ha, and moved with his new companion, Ghislaine Magnier, to Banyuls, where the couple began producing wine the following year. They would farm vines they owned on the steep schist of Banyuls, vinifying in a tiny cellar in Banyuls-sur-Mer, for the next twenty years.

From 2016 - 2022, following a split with Magnier and the sale of the Casot de Maiolles estate to Jordi Perez, Castex vinified in a rented cellar besides parcels he’d rented since 2005 in Les Aspres and Fourques.

In 2016, Castex began producing two cuvées from Spanish and Italian amphora: the white “Fleur d’Age” and the red “Fleur au Fusil.”

During this latter phase of his career, he farmed 2.5ha of very old vines, including carignan, grenache, merlot, mourvèdre, macabeu, grenache gris, l’oeillade, cincault, clairette, muscat d’Alexandrie, picpoul, and bourbelenc. He supplemented his own vineyards with the purchase of the yield of 1ha of syrah, farmed by the owner of his cellar, and a little merlot from Mataburro.

Yields in this latter period were between 25-30HL/ha.

The white “Tir à blanc” is foot trod and pressed very lightly. Its marc is returned to a tank to be covered with grey and red grapes, from which a rosé is drawn off before pressing. In such a way all his wines are sort of siblings from a given vintage.

Castex’s macerations last 4-5 days at maximum. Elevage occurs in tank or amphora and is relatively short, with almost all wines bottled and sold before the arrival of summer heat.

ALAIN CASTEX: AN INTERVIEW

This interview was conducted in October 2019. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.

When did you first becoming interested in making wine without additives?

ALAIN CASTEX: I started to make a little natural wine, to become sensitized to it, in 1991 or 1992. It was just tests. Not always conclusive ones! I would discover the world of natural wine later, in fact. But I was already interested in making wine without added sulfites, fermented on native yeasts, because of a meeting with Max Leglise.

At the time, he was retired, and he did conferences. It was in 1990 or 1991. At the time, there was an association in Béziers called Béziers Oenopole, and the director would bring in people to speak. He brought in Max Leglise and Claude Bourguignon. It opened a universe that I didn’t know.

This was before you encountered the natural wine community of the era?

I didn’t know anyone. I made natural wine in my corner. I didn’t know anyone did it elsewhere.

Then I truly fell into natural wine in 1997, when by chance I met Jean-Christophe Piquet-Boisson. He introduced me to Marcel Lapierre, Pierre Overnoy, and all those people.

Marcel was a bit crazy. They were party animals. It was hard to follow them in the Beaujolais. When we went to visit Marcel, you got out of the car and you had a glass in hand until the moment you went to sleep. You wound up in such a state…

Piquet-Boisson himself is quite intolerable, but I owe him that.

He’s a difficult guy.

He [acts like he’s] the inventor of natural wine. His personality is a bit blocked. He was influential once, but less so now. Because he completely marginalized himself. He didn’t want to see the evolution. We saw each other recently, at the party for the twentieth anniversay of La Guinelle vinegars in Banyuls. And he’s still just as intolerable.

He’s got a limitless ego. He went everywhere, and discovered many people. But then he stayed blocked, he didn’t accept that [natural wine] could expand outside of him. He would cut off the youth who arrived. It’s a story of taste, it’s his problem. At the start, he searched for new things; now what he sells is without interest. And the pioneer Marcel is no longer around, so there’s been a drift…

Happily there are new people who arrive, to launch the adventure. There are a lot of young people.

What made you leave Corbières?

It was love. I remade my life. For my new companion, Ghislaine, with whom I built Casot de Maiolles, it was a pity to stay [in Corbières]. Because I had built the estate there with my first wife. It was 13ha. It was too much.

At the time, in terms of natural wine in the south of France, it was just you and Bernard Bellahsen, from what I understand. When did you first meet the Bellahsens?

It must have been 1997, around then. I knew Bernard before knowing Marcel [Lapierre] and Pierre [Overnoy] and Emmanuel [Houillon]. And in the Loire, [Thierry ] Puzelat.

Little by little, I met everyone. Because at the start, in the Roussillon, there weren’t many people. Nowadays it’s good.

Here in the départment, there are many youth who arrive, who aren’t sons of vignerons. If they’re maybe not making natural wine, at least they’re farming organically. Then there are who pass into natural winemaking. It must be 60% of the new estate installations here.

And the [locals] flip, they don’t understand the movement. They’re still in their schema of productivism. They’re having difficulty following along. The bankers have understood. Because globally [natural] wines sell well. Those are the new estates that work well. Whereas in conventional [viticulture], it’s a catastrophe.

What’s the biggest challenge in terms of viticulture around Fourques?

We need water. We manage to make harvests with very little water. But its every year. There will be a moment when it becomes complicated. In Banyuls, it’s already complicated.

In the Hérault, it’s dry too. Here, it rains quite a bit on the Albères, where Jean-François Nicq and Yoyo are. Because they’re near the mountains, the clouds get blocked, and it makes water. Whereas us, here, it’s a cork tree forest, a dry forest. You have to go closer to the Massif de Canigou, there it rains more.

Your method of vatting red harvest atop white marc is very interesting. Can you elaborate on it?

When I press the whites, I don’t [break up the cake and repress], so there’s a lot of juice [in the marc]. So I put it back in the tank. Then I harvest my gray grapes, and then my reds, and little by little it fills up. And then I draw off the juice.

It’s a short maceration. But the interest in doing layers like that, with the less colored and less tannic grapes down there at the bottom, is the juice passes through it all, and it permits a longer maceration of the white and the grey grapes. They don’t add color, and the red juice passing through them takes the perfumes. It makes an assemblage.

When I de-vat, the whites are pink, because they’ve absorbed the tannins of the reds. And the grays are red.

Throughout the course of your career, natural wine has become a global phenomenon. When did you realize that this community of vignerons had become so influential?

There is a movement. It’s not very fast, but voila. When we started we represented nothing [in terms of volume], even if now we still don’t represent much. In volume, we must represent 0.08% of French wine production. But the press speaks more about our movement than all the rest ! That means we must represent something.

Now there are people who sell reverse osmosis machines, who explain that with them we can make a wine without additives, a practically “natural wine.” That means that our [original] idea was good. It corresponds to a demand.

The grand public is not yet totally up to speed with what they eat. Globally, people eat chicken from concentration camps, and it’s the same with eggs. So the more people become aware of that, the more the agro-alimentary system needs to adapt, if they want to make money. Because people finally realize that they’re eating industrial things, dead food.

Little by little, we return to things that are more natural. With more taste. And if there are more farmers who produce things with a good agriculture, then maybe people can choose to buy better things.

I heard a very amusing story about you and Thierry Puzelat getting into a fight at Marcel Lapierre’s wake.

We had drank a bit too much. Marcel, the number of times he got in fights, or got beat up… The worst was with Pierre Breton. Marcel couldn’t stand him. And, systematically, as soon as he could, he got in fights with him. In the Beaujolais, they start fighting as soon as they’re drunk. In the Loire, too, they’re hot-blooded. Here it’s calm. We drink less. But they’re crazies there. It’s tradition, you know.

FIN

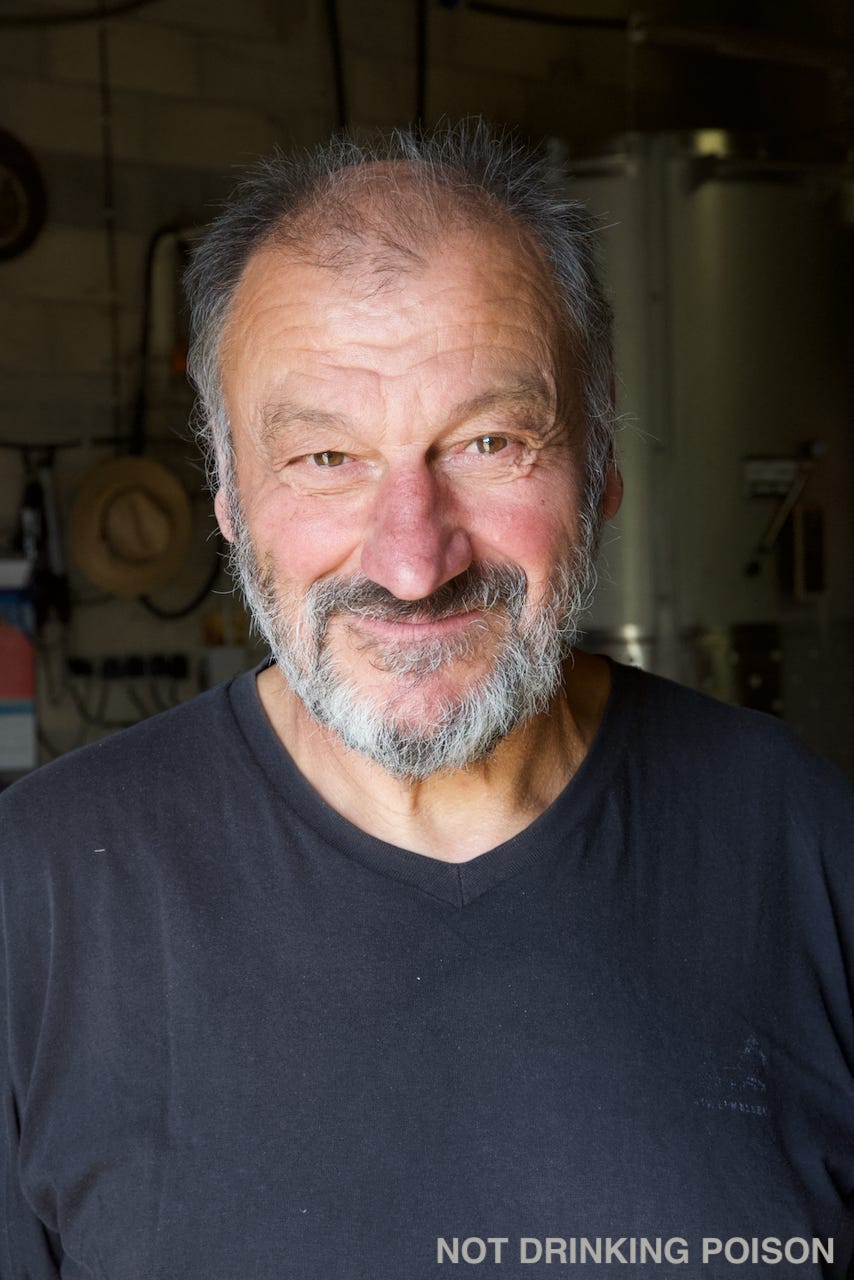

Alain Castex, vigneron.

1949-2023

FURTHER READING

A very touching 2005 post on Casot de Mailloles at Wine Terroirs.

Now if, say, Mathieu Lapierre (or someone of his generation) were to get into a fistfight with Puzelat at Castex’s wake, the circle would be unbroken.

Thank you for this.

And now I have another natural wine definition to add to the list I’m keeping (for fun): “What is natural wine? It is Thierry Puzelat getting into a fistfight with Alain Castex at the wake of Marcel Lapierre.1 “