Is A "Pét-Nat Opener" Necessary?

Hungarian design company Sekhina's new device is an imperfect solution to something that shouldn’t be a problem. But it is very handsome.

Recently the Budapest-based design company Sekhina contacted me with the offer to test a device they’ve created to aid in opening bottles of undisgorged pétillants naturels. Their straightforwardly-dubbed “Pét-Nat Opener” promises to allow anyone to “easily open an undisgorged high-pressure pét-nat without trouble and not wasting any juice and flavor.” [Sic.]

On a notional level, given the widespread availability of bottle-openers, corkscrews, and cigarette lighters, the act of marketing a new device to open bottle caps is sort of funny. It’s like suggesting a revolutionary new way to scoop ice cream, or drain pasta.

If the existence of Sekhina’s device nonetheless feels meaningful, it is as evidence of the wayward evolution of pét-nat culture ever since the wine style went global over the last decade or so. Sekhina’s Pét-Nat Opener is composed of just three pieces1, but there is, as the cliché goes, a lot to unpack.

THE ASSUMPTION OF NON-DISGORGEMENT

“As a result of the high pressure inside the bottle, it can be complicated and messy to open an undisgorged pét-nat,” Sekhina’s ad copy explains. “For this reason, this delicious drink is often excluded from gastronomic events and venues.”

Undisgorged, high-pressure pét-nats are indeed very difficult to open in restaurant service: this is why competent winemakers either disgorge pét-nats before shipping them to clients, or bottle said pét-nats with less residual sugar so as to result in less pressure. In efforts to identify a problem requiring a solution, the Pét-Nat Opener’s inventor has, in effect, excused winemakers from winemaking.

Disgorgement was a subject of debate among the chief originators of the contemporary pét-nat revival, back in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the Loire Valley. The late vigneron Christian Chaussard, who most credit with coining the phrase “pét-nat,” initially preferred not to disgorge his wines. Later he came around to preferring disgorgement, like his friend Pascal Potaire of Les Capriades. Among the main reasons was the difficulty of tasting sparkling wines suffused with lees.

As Potaire puts it nowadays: “If you put all the lees in suspension with gas, its effectively undrinkable.”

THE ALLURE OF NON-DISGORGEMENT

Casual observers of the natural wine scene over the past decade will nonetheless have noted a flood of leesy undisgorged pét-nats appearing on the market, particularly from the USA, Italy, Spain, and Central Europe. Before addressing the situation - with a device like Sekhina’s, for example - it’s worth examining how it came to be.

For a winemaker, there are three primary reasons to refrain from disgorging pét-nats.

For one, the presence of suspended lees in a pét-nat can provide an agreeable sensation of body and sweetness in wines that might otherwise scan as meagre and thin (whether due to overcropping or irrigation or inclement climate or some combination thereof).

Another reason, far more salient, is that disgorgement is messy and time-consuming, and most winemakers would prefer not to bother, particularly when (as is too often the case) they intend their pét-nats to be nothing more than inexpensive thirst-quenchers.

Finally, winemakers might refrain from disgorging a pét-nat if they wish to encourage further bottle-aging in consumers’ cellars, since undisgorged pét-nats are fairly immortal, preserved from oxidation by both CO2 and continued contact with reductive lees.

In practice this last consideration is rare to non-existent. Only two potential examples spring to mind.

One is Murcia winemaker Erik Rosdahl, whose wines I had the pleasure of working with during my brief stint doing the wine program at Table de Bruno Verjus. Rosdahl’s undecanted wine musts, bottled under crown cap, wholesale for somewhere in the 50€ range ex-cellar; Verjus charged 399€ for a bottle on his wine list.2

When I took the time to place Rosdahl’s pét-nats upside-down in a fridge for a day or two and subsequently disgorged them in a basin of water before service, they were limpid and tasted like manna from heaven. Served without prior disgorgement, they tasted like, and resembled, mud.

THE WORLD’S FIRST PET-NAT OPENER

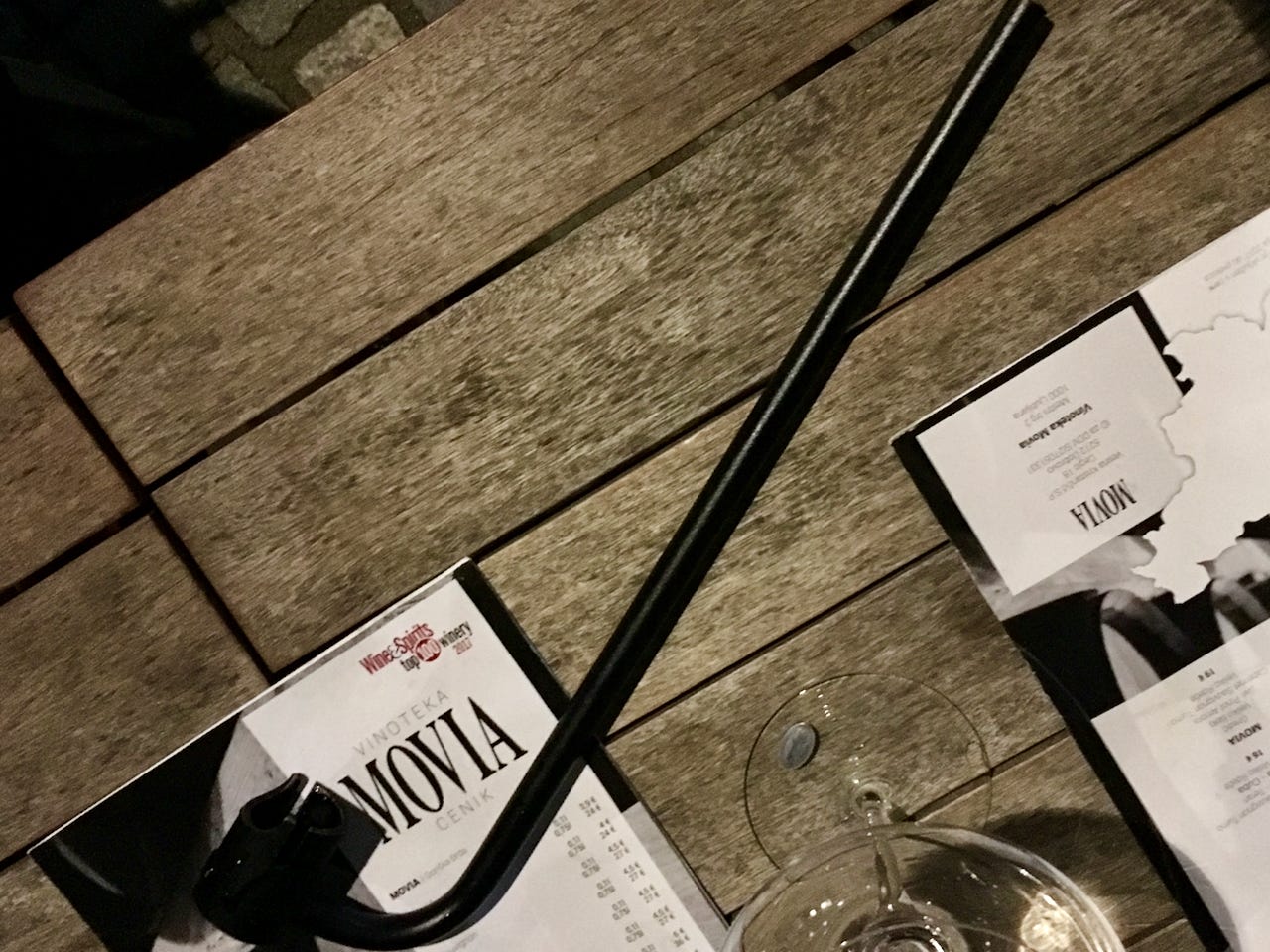

Bath disgorgement is a habit I picked up in 2006 at Pizzeria Mozza in Los Angeles, where we went through cases upon cases of “Puro,” the undisgorged crémant of Slovenian vigneron Aleš Kristančič, in his time surely the most well-known promoter of non-disgorged, age-worthy sparkling wine.

Kristančič accompanied the launch of “Puro” with a quixotically comprehensive educational spiel instructing sommeliers how to practice bath disgorgement with a Movia-branded tool, one that can lay marginally greater claim than Sekhina’s device to being “The World’s First Pet Nat Opener.”

There is a name for this tool. It is called a clé á dégorger and it is widely available at winemaking supply stores. It does help in practicing bath disgorgement or disgorgement à la volée, but in a pinch both actions can be performed with somewhat less precision with a normal bottle opener.

That’s how we did it back at Mozza. Our sommeliers routinely accidentally spritzed our guests with “Puro.”

It was, of course, a messy hassle serving the wine this way. But someone has to endure the messy hassle of disgorgement, if one wishes to serve a bottle-fermented wine in a manner that permits appreciation of its flavors and aroma (rather than those of its fermentary lees). Either the winemaker, or the hapless sommelier practicing bath disgorgement or disgorgement à la volée.

CAP PERFORATION

Sekhina’s Pét-Nat Opener operates by piecing a hole in the top of the bottle cap of an undisgorged pét-nat, and maintaining pressure upon the perforation by means of a screw system, thereby allowing CO2 to escape the bottle at a controlled rate.

While moderately amusing to watch, it is not a quick procedure. It takes five-to-ten minutes for enough CO2 to escape to permit removal of the bottle cap without risk of overflow. Of course, it depends on the individual bottle. For what it’s worth, we opened one of my own 2022 syrah pét-nats this way back in January using a hammer and a nail. It took about the same length of time for enough CO2 to escape.

This method of cap perforation - whether by hand or with Sekhina’s device - all but eliminates the risk of showering guests in pét-nat. But it fails to provide the clarifying benefits of disgorgement. Lees stay in the bottle and are thrown into suspension by CO2. This makes the Pét-Nat Opener somewhat inapt for opening bottles of good, terroir-driven pét-nat. Instead the device seems destined to ennoble, by means of its sophisticated concrete design, the service of imprecise, rush-job pét-nats intended as simple thirst-quenchers.

Is this progress?

“I would have thought, given the volume that we sell in France, that we’d have made the image of pét-nats evolve a bit more,” opined Pascal Potaire when I visited him in late May, shortly after learning that he and partner Moses Gadouche would close their estate. “To inspire newcomers [to producing pét-nats] to do the fundamental work.”

FURTHER READING

The Legacy of Les Capriades: An Interview with Pascal Potaire

Ceci N’Est Pas Un Blanc: Disgorging Pét-Nat Chez Andrea Calek and Stephana Nicolescou

My experience making my first pét-nat in 2021.

A 2008 blog post by Jeremy Parzen about bath disgorgement of Movia’s wines.

Not including a nifty tiny battery-powered contact lightbulb intended to illuminate bottles from below during service.

Disagreements over wine mark-ups contributed to the brevity of my stint chez Bruno Verjus.