Quentin Le Cleac'h Encourages Risk

Making the most of wayward wine fermentations with the artisan distiller, based in the Gard since 2017.

Originally from Brittany, Quentin Le Cleac’h (pronounced “clay-ahk”) became fascinated with distilling while living in a semi-autonomous commune in the Cevennes in the early 2010s. After a few years distilling with a partner in Faugères, he set up a solo operation in Saint-Quentin-la-Pôterie in 2017. Today he distills the wayward fermentations of friends and collaborators including Valentin Vallès, Sébastien Chatillon, Nicolas Renaud, Jean-François Coutelou, and more. Le Cleac’h’s yeoman’s work in creating quality craft spirits out of vinification failures effectively helps underwrite the Gard’s latter-day spirit of bold winemaking experimentation.

Quick Facts:

Quentin Le Cleac’h began distilling professionally in 2014, after taking over, with then-collaborator Martial Berthaud, the Faugères distillery of distiller and author Mathieu Fréçon, L’Atélier du Bouilleur, where Berthaud continues distilling today.

Since 2017, Quentin Le Cleac’h has run his own small distillery in the former cellar of his friend Sébastien Chatillon in Saint-Quentin-la-Pôterie.

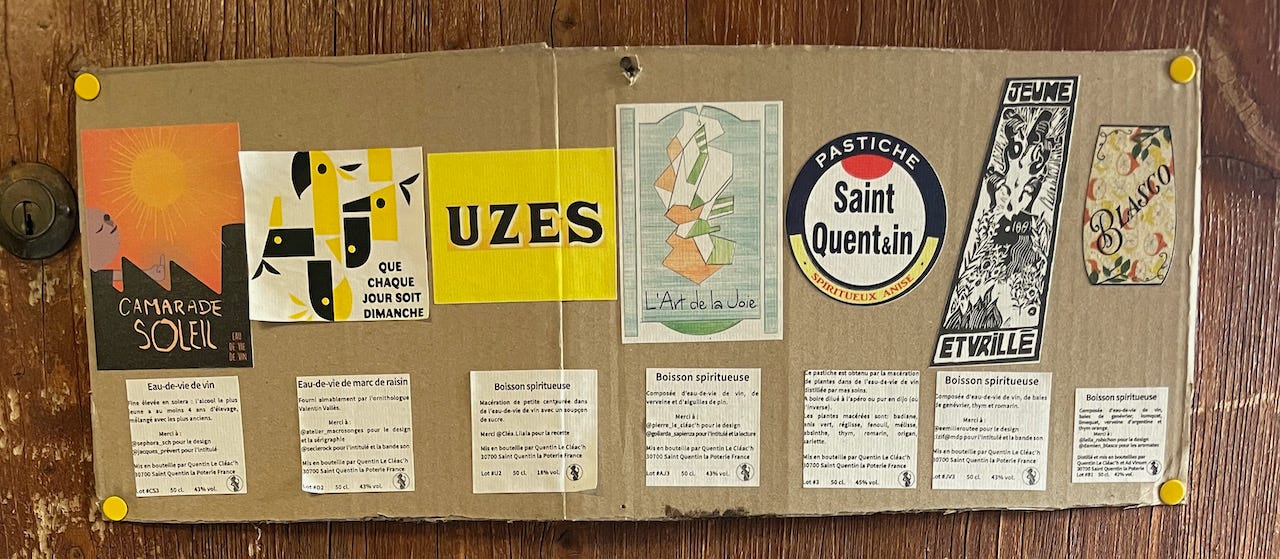

Le Cleac’h produces a broad range of spirits and liqueurs from distilled marc and wine, including barrel-aged wine brandy from a mini-solera; various marcs; a pastis; a natural, declassified gin distilled from wine; a range of infusions; and a clever variation on the liqueur Suzes called “Uzes.”

If, like many jaded journalists in search of ideas, you’ve ever wondered what’s the next big thing “after” natural wine, search no further. Natural spirits like those produced by Le Cleac’h and peers like Laurent Cazottes and La Distillerie du Petit Grain are primed for a renaissance, as more consumers learn to mistrust huge liquor brands in the same way they’ve learned to mistrust huge wine brands.

SALVAGE THE DAY

From nervous spouses, aggrieved fathers, shocked oenologists, and disapproving bankers, right down to the contractor overseeing the bottling line, or the disengaged, old-school importer, natural winemakers are invariably surrounded by people who discourage risk-taking in wine production.

Not Gard artisanal distiller Quentin Le Cleac’h. When fermentations go awry, he’s in a position to save the day, or at least salvage it.

As his friend Sébastien Chatillon put it, “You arrive at Quentin’s place and you see vats of spirits labelled with all the good vignerons of the area. They’re marked: Valentin Vallès, Nicolas Renaud, Ad Vinum, Fred Agneret, etc.”

It was after a Thursday afternoon tasting at Chatillon’s cellar in May that we drove the short distance to Chatillon’s former cellar in Saint-Quentin-la-Pôterie, where Le Cleac’h now works. Immediately upon meeting him, I understand that his popularity among natural vignerons isn’t founded entirely upon their need for his services. Le Cleac’h cuts an affecting figure; he has the open-faced sincerity of a young Jonathan Richman.

Jonathan Richman was a fan of the Velvet Underground before tracking down John Cale and getting him to produce The Modern Lovers. Le Cléac’h’s got into distilling in a similar way, via distiller and author Mathieu Fréçon, then based in Autignac.

“I like to party and drink, of course. And I was working in an autonomous community in the Cevennes, where we were doing everything ourselves,” he says. “I read a book about about distilling, and later the person who wrote the book suggested I take over his distillery.”

Occupying much of the lot beside Le Cleac’h’s workspace, when we arrive, is an immense, orderly pile of silver beer kegs, awaiting distillation into a whiskey-like product. (COVID-related restaurant shutdowns mean there will probably soon be a glut of whiskies from distilled beer on the market, as any craft beer brand worth its wort will be encouraging tap clients to exchange for fresher kegs after months of inactivity.)

Le Cleac’h is in the process of making more of his version of gin, a creation he punningly calls, “Jeune et vrillé,” or “young and twisted.” (Juniper, in French, is genevrier.) Triple-distilled from wine, the gin-like product infused with hand-collected juniper, thyme, and rosemary can nonetheless not be called “gin,” because it does not, and cannot, attain the minimum legal initial alcoholic strength, which, apparently thanks to industry lobbying efforts, has been defined in such a way as to be beyond the capacities of anyone working in a homemade, artisanal way with grape marc or wine (rather than corn, wheat, barley, rye, etc.). The final product clocks in at a similar alcoholic degree and flavor profile to “real” gin, only it has been produced from the natural sugars of organically treated grapes from natural vignerons in the Gard and the Landuedoc, rather than untraceable chemically-farmed grains.

I mention a similar product, Jeff Coutelou’s “Djinn,” only to learn that Le Cleac’h himself is the one responsible for producing it, along with Coutelou’s other spirits.

Le Cleac’h’s own range of spirits divides into three rough categories.

“Either I’ll age in it barrel, like a cognac, or I’ll do macerations, like the verveine, the Uzes, or the pastis, or I do a third distillation, with juniper, to make a gin,” he says.

I certainly see the commercial opportunity behind artisanal pastis, particularly in the south of France, where people pickle themselves in terrible anise almost year-round. (Le Cleac’h’s contains no less than fifteen macerated plants, almost all gleaned from the surrounding garrigue and his friends’ vineyards.)

But I profess to preferring Le Cleac’h’s eaux de vie and his gin to his macerations, which mostly scan like variations on mild limoncello. (Chatillon, for his part, is strikingly enthusiastic about those same macerations. I think it’s because they allow him, via collaboration with Le Cleac’h, to extend the creative streak he so enjoys in his own vinification period.) One exception is “L’Art de la Joie,” an eau de vie infused with verbena and pine needles that strikes an inspired accord worthy of a master perfumer.

Most revelatory of both Le Cleac’h’s art as a distiller and the nobility of his source material in the Gard is “Que Chaque Jour Soit Dimanche,” a lightly barrel-aged eau de vie from Valentin Vallès’ grape marc. It has a fruit and a fat reminisicent of Georgian chacha, a testament to the softness of Vallès’ vertical press work. (Traditional chaha is as delicious as it is because there is little or no press conducted in traditional qvevri winemaking; the marc retains much more personality.)

Le Cleac’h concurs. He’s grateful to work with the marc of a handful of winemakers who use softer vertical presses.

“Modern presses make eaux de vie that are too much on the vegetal side. There’s not the same fruit,” he says. “And it’s not the same yield. So you go through a lot of trouble for not much in the end.”

He makes sure to recover the marc immediately, as soon as it leaves the vertical press.

“You see the difference in the quality of the marc immediately,” he confirms.

I think, probably, many people have once wondered, when plied with conventional grappa after a large meal in some restaurant or other, why anyone would voluntarily pay to drink the stuff. Conventional distillates from mediocre source material pressed with modern presses are basically just firewater, all heat and no light. It’s worth seeking out something like “Que Chaque Jour Soit Dimanche” to see why the tradition of artisanal marc distillery got started in the first place - and why Le Cleac’h and others are reviving it.

“There are more and more of us who do this sort of thing. We don’t get in each others way, for now, which is good. There’s a lot of room in the market,” he says, when I invoke similar-minded peers like La Distillerie du Petit Grain and Laurent Cazottes.

“Already, he adds with a grin, “There’s a lot of natural wine to distill.”

Quentin Le Cleac’h

9, chemin de la Carrierasse

30700 SAINT-QUENTIN-LA-POTERIE

FURTHER READING

The website of Le Cleac’h initial inspiration, Mathieu Fréçon.